The mature practice of project management has become one of the key differentiators for integration companies that are interested in achieving long-term success.

Mature project management practices lead to increased profit, greater client satisfaction, higher employee morale and overall quality improvement. But many integrators treat the subject of project management as a person, not as a thought process.

They usually assign their best trouble-shooter (or lead technician) to the role of project manager because that person, they believe, will be able to pull the project out of the fire once a problem or crisis occurs. This strategy relies on that individual’s ability as a reactive problem-solver, but it doesn’t foster proactive planning and up-front communication. The professional project manager’s most important role is to keep the project’s interrelated elements in balance, maintaining its integrity as project changes, and variances begin to occur.

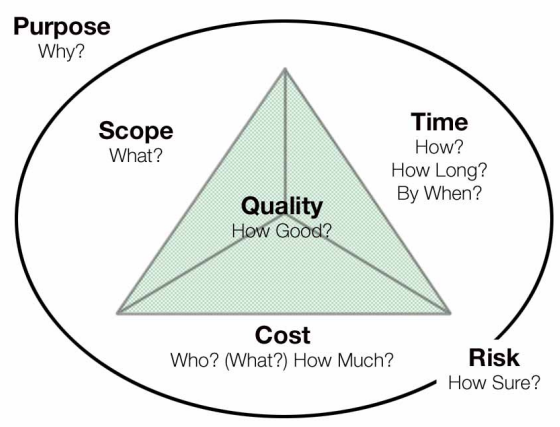

To help illustrate these interrelationships, think of a project as a three-sided pyramid (below, viewed from above) with five major elements.

These elements are initially generated by the salesperson, as part of the proposal or bid process, and handed over to the project manager upon contract award. These elements must then be kept in balance through the skills of the project manager. In other words, the sides of the pyramid must always stay connected, which isn’t the same as keeping them rigid and immovable.

The project manager’s role is also like that of a newspaper reporter — asking questions of key stakeholders to discover the answers that will make the project viable and successful. In addition, this creates “common sense” among the numerous people who will interact during the project’s implementation. Project managers must be aware that although they may think their personal opinions are important, they aren’t not the most important opinion or answer — that belongs to the client.

Let’s break down the five elements and consider the pertinent questions that project managers must ask.

But before we do that, someone needs to ask the client the most important question: “What is the purpose of this project?”

The client’s answer helps define the value that must be achieved, or the return on investment, from the client’s own perspective. Having this answer clearly defined provides meaningful criteria with which to make sound decisions later in the project when changes or variances begin to occur.

1. SCOPE

The first element is the SCOPE of the deliverable that your company will be providing to the client, whether that deliverable is a videoconference room, a home theater, a boardroom, or an auditorium.

And the question to be asked is, “What are we delivering?”

But sometimes more importantly, you need to ask, “What are we not delivering?”

You should be able to tie your deliverables back to the purpose of the project in a cohesive manner — each deliverable plays a part in achieving the desired value.

2. TIME

The second element is that of TIME, stemming from two questions.

The first is, “How will this deliverable be designed, installed, commissioned, trained for, etc.?”

This is a process or activity-based question, and the project manager relies on the integration company’s functional managers and process owners (engineering, installation, programming, etc.) for those answers. In a larger project, the project manager must also understand the activities of other trades and the interdependencies with the integrator’s activities.

The second question is, “How long will it take to deliver this project?” or “By when does the client need this project completed?”

These are duration-based conversations and are often determined or requested by the client.

“By when” projects will have a constrained end date, such as a school opening, board meeting, or a concert. Rental and staging companies will deal almost exclusively with fixed-date projects.

“How long” projects have flexibility in the timeline — the client would like the room completed sometime in the next 6 to 10 weeks, for example.

One of the worst things an integrator can start doing is turning flexible projects into fixed-date projects. This occurs when sales tells the client, “We can finish it in 6 weeks — no problem.”

3. COST

The third element is the COST associated with the resources and materials needed to accomplish the project’s deliverables.

This element also comprises three questions.

The first is, “Who is needed to fulfill this project?” It determines the skill set and competence required to accomplish the activities needed to fulfill the project’s deliverables.

The next cost question is, “What materials are required (plasma panels, cabling, microphones, racks, control systems, etc.)?”

This is followed by asking, “How much?” as it pertains both to the amount of hours needed from the project’s human resources, as well as the quantity of equipment, materials and parts required.

In my experience, the amount of human resource labor effort (including project management hours) required to fulfill a project is often underestimated, or it is collapsed into the duration (time) element. Example: “We’ve only got one day to do the project, so I bid 8 hours — although it’s a 100 miles away.” In this context, cost is very distinct from price — the client will be charged a price and the integrator will incur costs against that project.

In the ideal world, price will always exceed costs (if profit is important).

4. QUALITY

The fourth element, QUALITY, is the volume of the pyramid (the insides) and is dependent upon — and impacted by — the prior three elements: scope, time and cost.

The question that sales, engineering, implementation, and the project manager need to ask here is, “How good?” as it relates to each of the three sides of the pyramid.

- How good (well) do the deliverables have to function?

- What are the performance specifications, their desired reliability, maintainability, availability, ease of use, etc.?

- How good are the processes used to design, install, test, train, and commission the products and services to be delivered?

- Are there standards, procedures or guidelines in place that must be followed? Or does each individual do their assigned work his/her own way (the difference between personbased quality and process-based quality)?

- How good are the human resources to be used on the project?

- Have they been well trained and are they rewarded for performing in compliance with the established standards?

- How good are the parts and materials being used?

- Does each individual piece meet the desired quality specifications, or will the ultimate deliverable suffer because components and functions are of mix-match capabilities?

5. RISK

Finally, the fifth element is RISK, and it makes up the foundation of the project — or its stability and predictability.

When it comes to risk, project managers need to ask, “How sure are we about the conditions that could impact the outcome of this particular project?”

The more similar a project is to others the company has executed, the more predictable the outcome. Therefore, the project ought to be stable, the pyramid sitting on a firm foundation.

The more unique a project is (different materials, different client, different project team resources), the less predictable the outcome and weaker the project’s foundation. In order to make a project more stable (less risky), the project manager will typically have to tweak one of the other elements, whether to increase cost, increase time, decrease quality, or decrease scope.

In order to keep the project in balance, the project manager must also have flexibility in at least one of the primary elements (scope, time or cost). This flexibility is determined by prioritizing the three elements through a series of questions:

- Who has authority over which element? The client may have dictated the scope and time; therefore, the project manager needs to have authority over the cost element.

- Which primary element is most important to the client?

- Have these priorities been communicated? To whom? Is there agreement?

- Which element can vary (based on priority)?

- By how much can it vary (based on uncertainty — the more unique the project, the more flexibility required)?

- Which is constrained (typically scope, time and/or quality)? By whom? In the integration industry, scope and time (duration) are often fixed, or constrained by the client. So is the ultimate price. The price may be fixed at the beginning of a project by the sales organization, but the project manager must have flexibility in the costs of the project, especially regarding the amount of effort required by the project team resources.

The more unique the project, the wider the variance threshold required by the project manager. This does not mean they have the ability to authorize undisciplined changes to the scope of the project or its deliverables, but they must be allowed some measure of variance, based on the skill levels of the estimated resources vs. the skill levels of the actual resources assigned.